A Mordovian prison physician and his harsh treatment of Ukrainian prisoners

A Mordovian prison physician and his harsh treatment of Ukrainian prisoners

When you arrived, it would be like this:

You entered the reception room.

You were stripped to the skin.

You were shaved.

You were beaten with a truncheon.

Then you met Dr. Evil.

Pavlo remembers it well: “I was put in a bent-over pose and brought to get an X-ray. And at the X-ray there was this Dr. Evil, as we call him, shouting and with a stun gun.

“He started waving the stun gun, hit me a couple of times, began to threaten me, saying, ‘Hurry up, don’t be stupid.’ … He said that we ‘stinking Ukrainians’ didn’t deserve any decent treatment after what we had done.”

What had they done? Pavlo, and dozens of others trucked into this penal colony, had fought for their home country in the war that followed Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

Many of them had been captured after taking part in the desperate defense of Mariupol, a coastal city that was almost entirely destroyed by Russian bombardment. Its ruin, and the months-long siege of the massive Azovstal steel plant, where its last defenders holed up in increasingly desperate conditions, became a global symbol of the savagery of the war.

Now they were prisoners, deep within Russia.

There are an estimated 8,000 Ukrainian prisoners of war in Russia, along with civilian Ukrainian captives; thousands of other POWs have already returned home in organized prisoner swaps. Reports of their torture and abuse have been trickling out since the first group arrived back in Ukraine in 2022, and have kept coming with the release of additional prisoners.

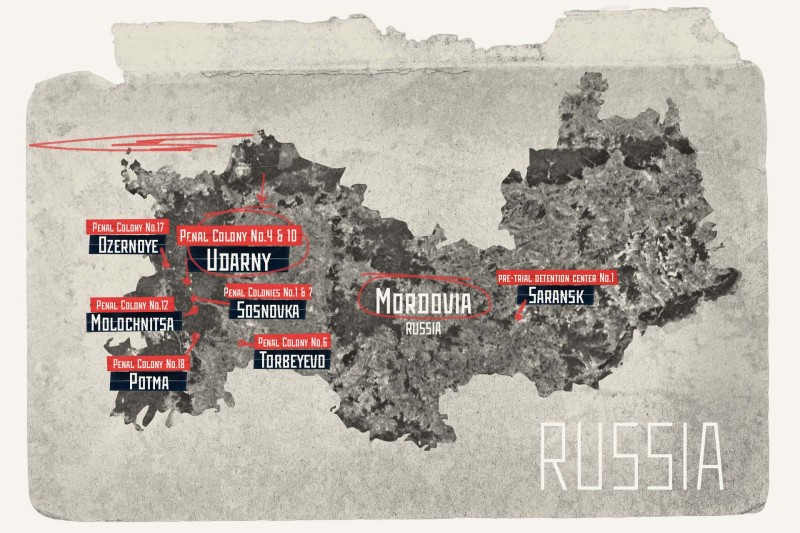

Returned POWs tended to report that one of the worst places to be held captive was Mordovia, a region in central Russia known for the many prisons and detention centers that dot its forested landscape, a legacy of the Soviet gulag system. Investigative journalists at Radio Free Europe’s Ukrainian service wanted to learn more about what was actually happening in these facilities.

Although Mordovia has over a dozen prisons, nearly all the Ukrainian POWs sent there were held in a facility called Penal Colony No. 10, a large complex that sits along a road cutting through a forest, more than 500 kilometers from the Ukrainian border.

Reporters obtained a list of 177 Ukrainians who had been held at Penal Colony No. 10 from sources in Ukrainian law enforcement. Nearly all, according to Ukrainian officials who interviewed them when they returned home, reported having been tortured and subjected to relentless physical and psychological violence. So reporters started reaching out to hear their stories.

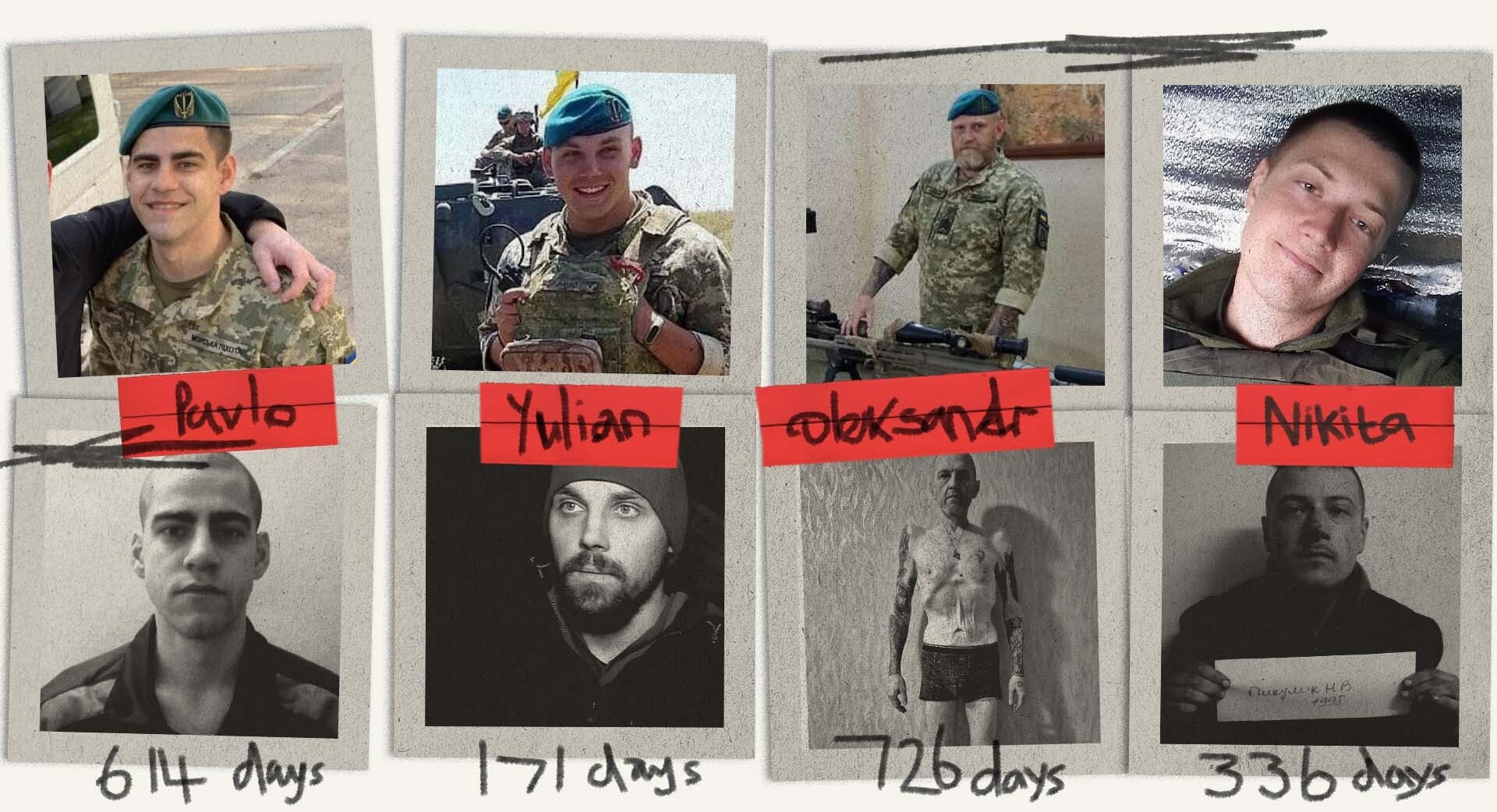

There was Pavlo Afisov, a military school graduate from the north of Ukraine who spent 614 days in Colony No. 10., along with stints in other Russian prisons. Yulian Pylypey, who still has a scar on his forehead after his captors set an attack dog on him and spent 171 days in the colony. Oleksandr Kiriienko, who sports a Viking beard and has served in the Ukrainian army since 2014, was there for 726 days. And Nikita Pikulyk, a young man with a boyish face who was captured after he had slipped out of Mariupol in civilian clothes. He spent 336 days in Mordovia.

Forty-six other POWs also agreed to speak about their experiences.

Physical torture was a given, they said. There were constant beatings, often targeting their backs and kidneys, for the smallest perceived infraction.

They spoke of the tools most commonly used against them:

Garbage bags were put over their heads.

Stun guns were used to administer shock after shock.

Attack dogs were set loose on them.

Thick plastic pipes were used to beat them

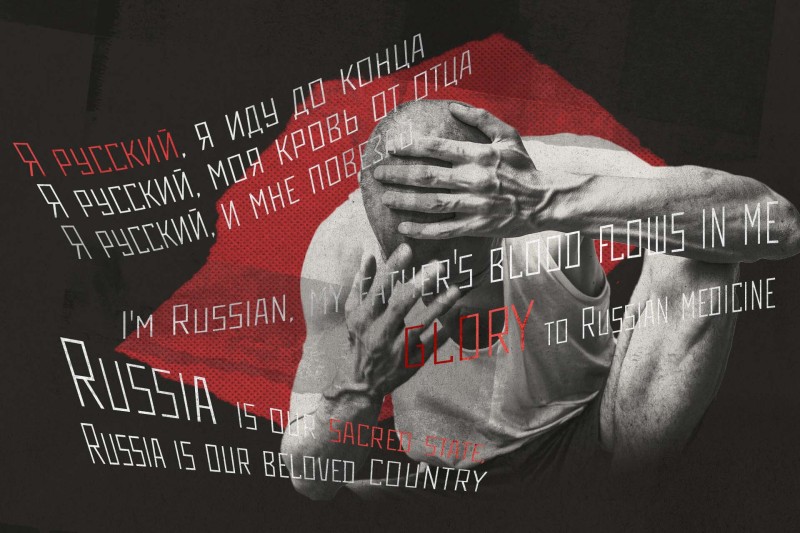

They also described rampant sexual violence — threats of rape, beatings aimed at their genitals — and psychological torture, like mock executions. They said they were forced to stand for up to 16 hours a day, listen to loud Russian patriotic songs for equally long stretches (or 24 hours straight, if they were in the punishment block), and sometimes sing along to the Russian national anthem, hands on hearts.

"You’d want to say, ‘Just beat me. Let 10 of you beat me with batons for five minutes. Then I’ll lie down, moaning, but in silence — please.’” - Yulian Pylypey

In all the stories these men told, an additional detail kept coming up. All 50 former prisoners referred to one memorable figure in Colony No. 10 — not a prison guard or administrator, not a military officer, but a doctor.

Nobody knew his name, but they all called him by the same nickname: Доктор Зло, or Dr. Evil.

Some of them also called him “the psychopath.”

He wore a white coat and usually hid his face behind a medical mask or a balaclava, but the prisoners said his voice was unforgettable.

“It was manic, screechy,” one said. “Indescribable.”

Most of the prisoners said they encountered Dr. Evil immediately after their “reception” at the colony, since they had to undergo a chest X-ray when they arrived — Russian prisons are rife with tuberculosis — and this man usually administered it.

He also used the occasion to administer electric shocks to prisoners, several of them recalled — and would continue shocking them over the course of their captivity.

Although the prisoners were soldiers, accustomed to violence and braced for cruel treatment at the hands of their captors, they said the doctor stood out because of his pointless sadism and seeming betrayal of medical principles.

Yes, he hit sick [prisoners] on the hands with a shocker, instead of giving them medical help, giving them pills or necessary medications. That is, he’s a completely psychologically ill person, who somehow, I don’t know how, ended up in this medical sphere. If it was just the guards, or federal penitentiary workers, or security guys, then, okay, you could understand anything from them. But this kind of treatment from medical staff was very hard for us to understand. - Nikita Pikulyk

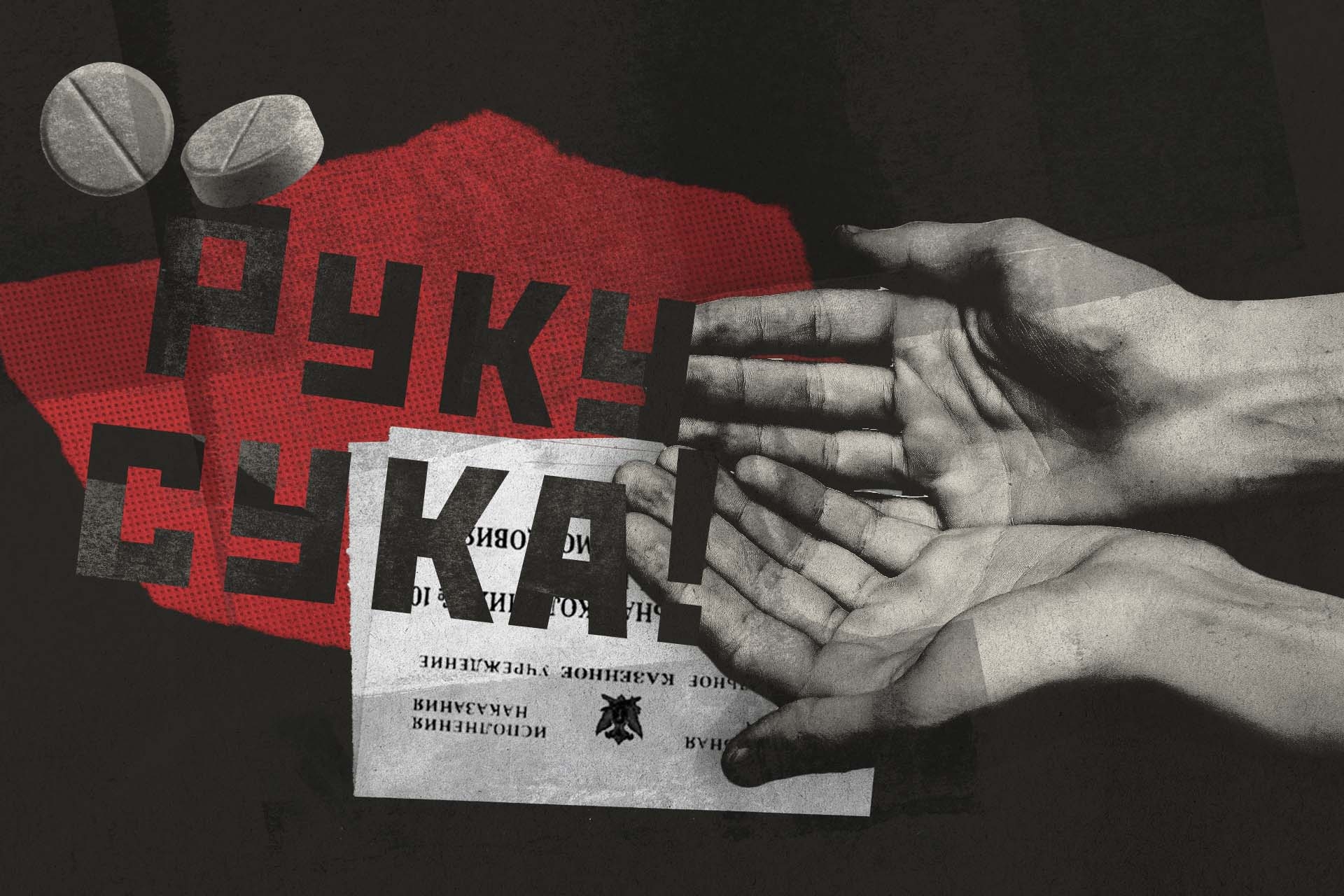

“Dr. Evil” would visit the prisoners’ barracks at unpredictable times — it might be during an inspection, or it might be at random.

It might be to dispense medicines — which he would do by ordering prisoners to drop to their knees and extend their hands.

“Hand, bitch!” prisoners recalled him shouting.

But just as often, prisoners said, their outstretched hands would be shocked with a stun gun, the promised pills never received.

"’Now I’ll experiment," Yulian Pylypey recalls him saying, before turning the stun gun to "maximum."

Oleksandr Kiriienko also remembers what would happen if anyone asked for medical help: “Whoever turned to him, he always carried a stun gun. Yes, the door would open, and whoever had asked for him — he’d hit them with the stun gun and say, “Will you ask for a pill again?”

"Of course, the answer was ’no.’"

But more disconcerting, the men all said, was the relentless psychological abuse the doctor subjected them to.

He made the prisoners bark and crawl across the floor like dogs, they recalled. At other times they were ordered to imitate roosters: “Cock-a-doodle-doo, guys, cock-a-doodle-doo!”

One Ukrainian POW had the unfortunate distinction of being especially good at barking. He came in for special attention.

"Every time someone passed by, he had to bark. God forbid he didn’t. The doctor would immediately shout: ‘You, bark!’” - Yulian Pylypey

Also unforgettable, the prisoners said, was how the doctor forced them to sing Russian songs for hours on end, or chant strange, repetitive slogans or stock phrases from pop culture. While they were speaking their lines, he would walk among them with his stun gun and shock them, seemingly at random.

Most of the doctor’s catchphrases made no sense — they seemed meant only to degrade.

“He would shout ‘Yogurt!’ and we would have to shout ‘Danone!’" explained Pavlo.

“He would shout ‘Danone!’ and the prisoners would have to answer, ‘Mmm!’”

“Pepsi!”

“Pshhhhh!”

“Who lives under the sea?”

“Spongebob SquarePants!”

Others had a meaning that was all too clear.

“His favorite question for all of us was, “Who are you?”

We had to reply, “Faggots.” - Pavlo Afisov

The doctor also demanded that prisoners shout out praise for Russian doctors — and the entire medical profession. If they didn’t say "Glory to Russian medicine!" every time he prompted them, "there would be consequences," Nikita Pikulyk recalled.

The consequences? "Best case, you get shocked a few times by the doctor," said Yulian Pylypey. In the worst cases, special forces would be called into the cell to "educate" the prisoners.

Oleksandr Savov, another POW, recalled that he was showing signs of tuberculosis when he entered the colony. He assumed he would be isolated, or receive medical help. Instead, he encountered Dr. Evil — who shocked him with a stun gun and called him a “faggot.” He remembers the doctor asking him, “Aren’t you going to scream?” and shocking him again.

“What, am I supposed to scream?” he remembers asking.

“‘Glory to Russian medicine,’” the doctor prompted him.

“So I shouted, ‘Glory to Russian medicine!’ … and again, he used the shocker.”

"Every time he came, he’d make the whole block shout, ‘Glory to Russian medicine!’" - Pavlo Afisov

Mistreatment of POWs, whether it’s physical abuse or “humiliating and degrading treatment,” is a violation of the Geneva Conventions. Although it may be counterintuitive, victims of abuse in detention centers often report that degradation at the hands of their captors is more scarring than many forms of physical torture.

“[V]ictims always referred to this humiliation as a central part of what they went through and of what actually damaged them deeply,” said Thierry Cruvellier, a French journalist who has covered international justice and war crimes around the world for over two decades.

“Screaming nonsense, reciting poems or songs — to me, it was one of the most degrading things. Honestly, I would rather be hit with a baton 10 times than do that.” - Yulian Pylypey

By all accounts, Ukrainian POWs in Russia appear to have been subjected to especially pervasive abuse, coordinated from the top down.

The Wall Street Journal reported in February that prison guards in Russia had been instructed to “be cruel” to Ukrainian POWs. Citing three former prison officials who fled Russia, including two special forces officers and a member of a medical team, the Journal said that a group of elite prison guards received orders that “normal rules” would not apply to prisoners of war. The guards were then circulated to prisons across the country that received POWs, to work with lower-level prison officials.

In a report the following month, Amnesty International also found evidence of systematic torture and denial of medical treatment to POWs, as well as other alleged violations of the Geneva Conventions.

“In all wars, you have abuse of prisoners of war,” said Cruvellier. “I don’t think I know of any that haven’t gone through this…. What is exceptional in this particular case is that it is systemic, and often of high intensity.”

Despite all the attention he paid them, the prisoners said that the man they knew as Dr. Evil did not actually treat their ailments. One man, who had a rotting tooth that caused him agonizing pain, begged for painkillers, only to be denied. (Although medical care in Russian prisons does not tend to get good reviews in the best of times, prisoners said that another doctor at Colony No. 10 would treat them sometimes — “when he was in a good mood.”).

A man named Volodymyr Yykhymenko died at the prison. His cellmate, Valentyn Poliansky, told reporters that Volodymyr had been beaten across the face and ears with a slipper a few days before his death, causing his ear to swell and bleed alarmingly.

Poliansky said the prisoners asked Dr. Evil to examine the man’s ear, but the doctor refused.

(On Yykhymenko’s Russian death certificate, his cause of death is recorded as ventricular failure. A Ukrainian death certificate confirms that he died from pneumonia, but makes note of hemorrhages and abrasions he suffered two to seven days before his death.)

"If you ask for, say, a bandage to dress a wound or a pill for a toothache, you’ll be told, ’There’s no doctor.’

"You could absolutely never approach Dr. Evil. He didn’t treat anyone.” - Pavlo Afisov

After learning all this, reporters decided to see if they could discover the real identity of this unusual figure — obsessed with chants, slogans, and obedience — who had made such an impression on these battle-hardened prisoners of war.

Reporters started with one clear fact: Medical services for Penal Colony No. 10 were provided by a specific unit of Russia’s Federal Penitentiary Service, Medical Unit No. 13. Any doctor working at the prison would have come from there.

Searching through Russia’s most popular social network, a Facebook clone called VKontakte, they found all the pages that mentioned the abbreviation for the unit, “MSCh-13.” Among them was a page for the unit itself, two pages for the federal penitentiary service in Mordovia, and a page for the Mordovian trade union of state sector workers.

They gathered dozens of photos from these pages, showing the medics receiving awards, assembling for group photos on professional holidays, and posing stiffly in front of their workplaces.

There were even a few video clips, showing them dancing and singing in celebration of a Russian holiday for medical workers, and another one called “Day of the Medical Service of the Penal System.”

Reporters started identifying the medical staff of the prison — many were connected via social networks — and sharing these photographs and videos with the former POWs, to see if they recognized any of them.

The first reaction came from Pavlo Afisov. As soon as he heard the voices in one of the video clips, he started calling RFE/RL reporters, even though they had never spoken on the phone before. He was emotional.Hi

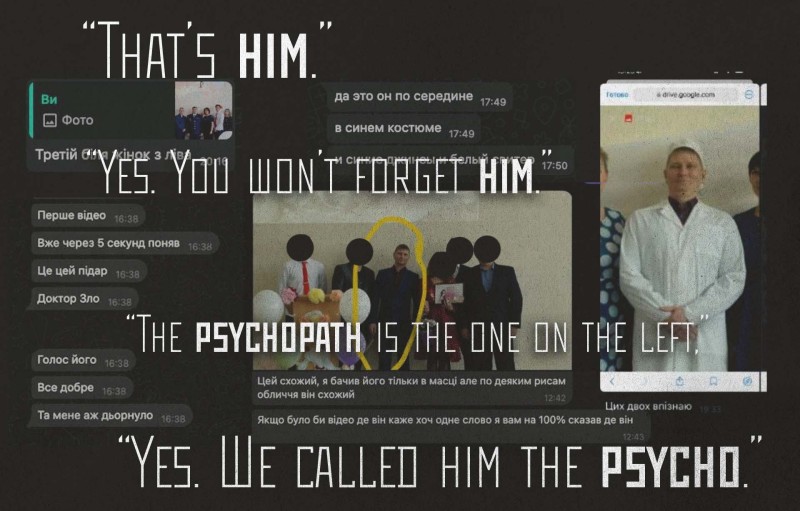

Soon, Yulian Pylypey also chimed in. He cropped out an image of one doctor, a blonde man with a bowl cut and a white lab coat who had featured heavily in the photos and video clips found online.

“The psychopath is the one on the left,” he wrote.

Both men were completely certain that they were seeing and hearing Dr. Evil.

To confirm the identification, reporters asked the other 48 former prisoners if they recognized the man in the photographs and videos. All of them said they did.

But who was this man?

Meet Ilya Sorokin. He is 34 years old. He’s married, with two daughters. He was born in the small Mordovian village of Potma, just 30 kilometers from Penal Colony No.10, and still lives there today. Records show he started studying at a local medical school in 2008. According to the research tool Himera-Search, which archives information leaked from Russia’s interior ministry and other databases, Sorokin has been working as a prison doctor since at least 2018, making around 564,000 rubles a year (around $9,000 at the time).

Prison doctors in Russia tend to be hired out of small public clinics in rural areas, where salaries are even lower, according to Olga Romanova, the founder of prisoner-rights advocacy group Russia Behind Bars. Landing a job with the federal penitentiary service, or FSIN, means an immediate boost in status as well as salary.

But becoming part of the FSIN system also means that doctors join a militarized agency — literally “put on epaulettes,” as Russians say — and their superiors become military officers.

“To get more money, they put on epaulettes, they go work for the FSIN, and they get a bonus for their military rank — their salary approximately doubles — and that’s what they really want, in the provinces, to work in prisons and prison hospitals,” Romanova said, suggesting that this opened up Russia’s prison medical system to abuses.

“They’re all FSIN staff first, and doctors second,” she said. “They report to the leadership — the FSIN leadership, not medical leadership.”

Sorokin’s online presence — personal profiles on VKontakte and Odnoklasniki — helps sketch a rough outline of his life. Photographs of him as a young man show him living what seems to be a modest lifestyle typical of the Russian provinces. They give way to images of him studying medicine, clad in a typical white coat and Russian doctor’s cap and goofing around with medical props like IVs and a model of a human skull. He got married in around 2012. Six years later, he and his wife drove hours across Russia to visit the new Crimean Bridge — a symbol of Russia’s takeover of the Crimean Peninsula — just a few days after it opened.

His social media posts also give a glimpse of his personality. He is sentimental (“I love and adore my wifey!” he said in one status update), and appears nostalgic for the Soviet Union’s glory days, participating in military parades on the patriotic Russian holiday May 9 and even dressing up in Soviet-era military garb. He’s also a booster of the current war, posting messages of support for the Russian army and insignia with the “Z” symbol, which conveys strong support for Putin’s military agenda.

He appears to take pride in his role as a doctor.

“Happy Medical Worker Day!” read a post he shared in 2012, illustrated with a cartoonish image of a scantily clad nurse. Another post showed his name spelled out in Cyrillic characters, with sexy nurses draped over each letter.

But there’s not much to set him apart from any one of the millions of other Russians who support the war, celebrate national holidays, love their wives, and appreciate nurses. The most notable thing about Ilya Sorokin might be how ordinary he seems.

In her classic study of the trial of Nazi official Adolf Eichmann, philosopher Hannah Arendt explored how the architect of the Holocaust came across not as a fanatic, but as a bureaucrat — a “terrifyingly normal” man who took comfort in following rules, climbing the career ladder, parroting cliches, and joining organizations to help give himself a sense of identity.

This appears to be an apt description of Sorokin, too. Online, he is a member of several social media groups for doctors and penitentiary workers. In his real life, too, he appears to have been an avid joiner of groups and committees. According to a post from the state worker’s trade union, Sorokin served on the “profkom,” or governing committee, of the union for Medical Unit No. 13. He was also a member of the Mordovia-wide trade union committee.

“He took an active part in the life of the team, in amateur performances,” the post read.

Indeed, social media pages from the medical unit and affiliated organizations show that the doctors were enthusiastic about pageants and performances. Sorokin appears in several. In one, he is wearing a dark wig and draped in leaves.

A caption under the photo wishes him a happy birthday: "Today is the birthday of the secretary of the Primary Trade Union Organization of Federal State Health Care Institution Medical-Sanitary Unit #13 of the Federal Penitentiary Service of Russia, Ilya Sorokin! With our whole heart we congratulate Ilya on his holiday! We hope he stays just as responsive, benevolent, and active as he is!!"

In another, he performs a medical-themed comedy bit alongside a female nurse, pretending they are about to perform an operation.

"So, shall we begin?" he asks her. "Scalpel — uh, i mean, tablecloth? Flowers?”

“Here!”

“Alcohol — uh, i mean, antiseptic?”

“Here!”

A clip of Sorokin’s skit in honor of "Day of the Medical Service of the Penal System.”

In 2022, he was even recognized by Mordovia trade union committee "for conscientious fulfillment of civic duties and active participation in the life of the team,” according to a certificate he posted on social media.

Until recently, he openly indicated his workplace on social media as “Medical and Sanitary Unit No. 13 of the Federal Penitentiary Service of Russia.” Now, it has changed to say “Armed Forces of the Russian Federation.”

In late 2024, Sorokin joined the Russian military and went to war as a company medical instructor, according to a social media post from the Mordovian Trade Union of State Agency Workers.

He took the call sign “Doctor,” the post said.

A human resources specialist at Medical and Sanitary Unit No. 13 confirmed that Sorokin was part of the unit, and had a “position reserved for him” after his time in the military came to an end.

Reporters reached out to Ilya Sorokin to see if he wanted to comment on their findings. The conversation was brief.

Ilya Sorokin: Hello.

Journalist: Hello, Ilya, good afternoon. My name is Olha, I’m a journalist with Radio Liberty. I wanted to ask you: Ukrainian servicemen returning from captivity in Russia, who were held at Penal Colony No. 10, identify you as the person who tortured and beat them.

Ilya Sorokin: That can’t be true. I don’t work there.

Journalist: You don’t work there?

At that point, he hung up. After two more attempts to reach him, he blocked the number.

The FSIN and the administration of Colony No. 10 did not respond to requests for comment. Russian officials have publicly maintained that POWs in the country are treated humanely.

Now back in Ukraine, the former prisoners of war who told of suffering at the doctor’s hands are trying to put the torments of the past few years behind them.

Some of them are fixated on exposing their tormentors. Others just want to forget. Afisov recently arrived in Italy for treatment, a country he had long dreamed of visiting.

But many of them still recall the camaraderie of their days in captivity, and how the Ukrainians in Colony No. 10 supported each other — through songs and music of their own.

At night during the Christmas holidays, Yulian Pylypey recalled, the men would try to sing carols together.

"Some of the guys were also from Western Ukraine, where these traditions are more common. They knew a few carols by heart. We knew the date, and we sat down and quietly began to sing together. There were eight of us in the cell at that time. We started singing the carol, then added blessings. While we were singing, a guard came by and knocked on the cell door, shouting:

"Shut up!"

We paused for a second — then started singing again, but more quietly. Because the moral, spiritual part — when you’re in captivity — is the most important.

You must keep that strength of spirit alive.

And so you sing."

Смотреть все новости автора

Распечатать